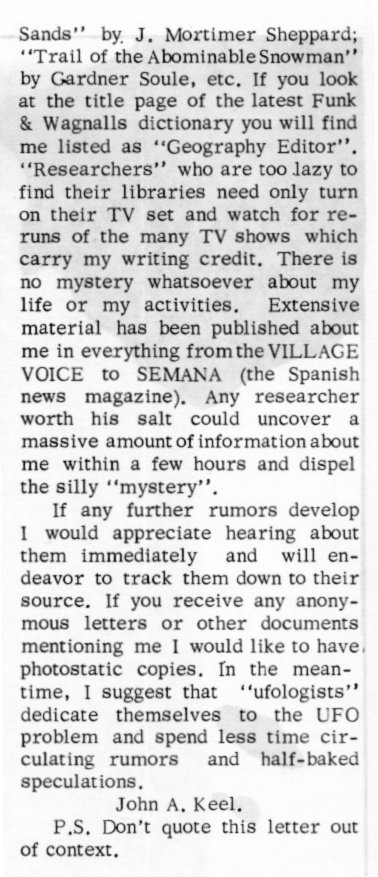

As John said in the letter I posted last week, he was mentioned in several books, including Cocktail Party for the Author by Alex Jackinson. Jackinson’s book is a memoir of his ten years as a literary agent, published by Challenge Press in 1964. He was John’s agent in the ’50s; he advised John on writing for men’s magazines, and eventually sold Jadoo to Julian Messner. I found a copy of the book (it’s not rare) and read it. He devotes the third chapter to John, heading it with a question that must occur to many readers of Jadoo: “How True Are the True Adventures?” The answer, not surprisingly, is rather complicated.

Jackinson seems to have been an interesting character. He came from a Russian Jewish family, who emigrated to the Bronx in 1913. His father was a garment cutter; his uncle, Morris Terman, was an editor and writer active in left-wing politics and Yiddish literature. Young Alex became a cutter like his father (he specialized in furs), but was inspired by his uncle’s literary interests. He wrote (and sold) work in many genres: poetry, song lyrics, romance and detective stories. He opened a literary agency in 1953, and was particularly sympathetic to small publishers and young writers. He began by helping his fellow poets to write commercially.

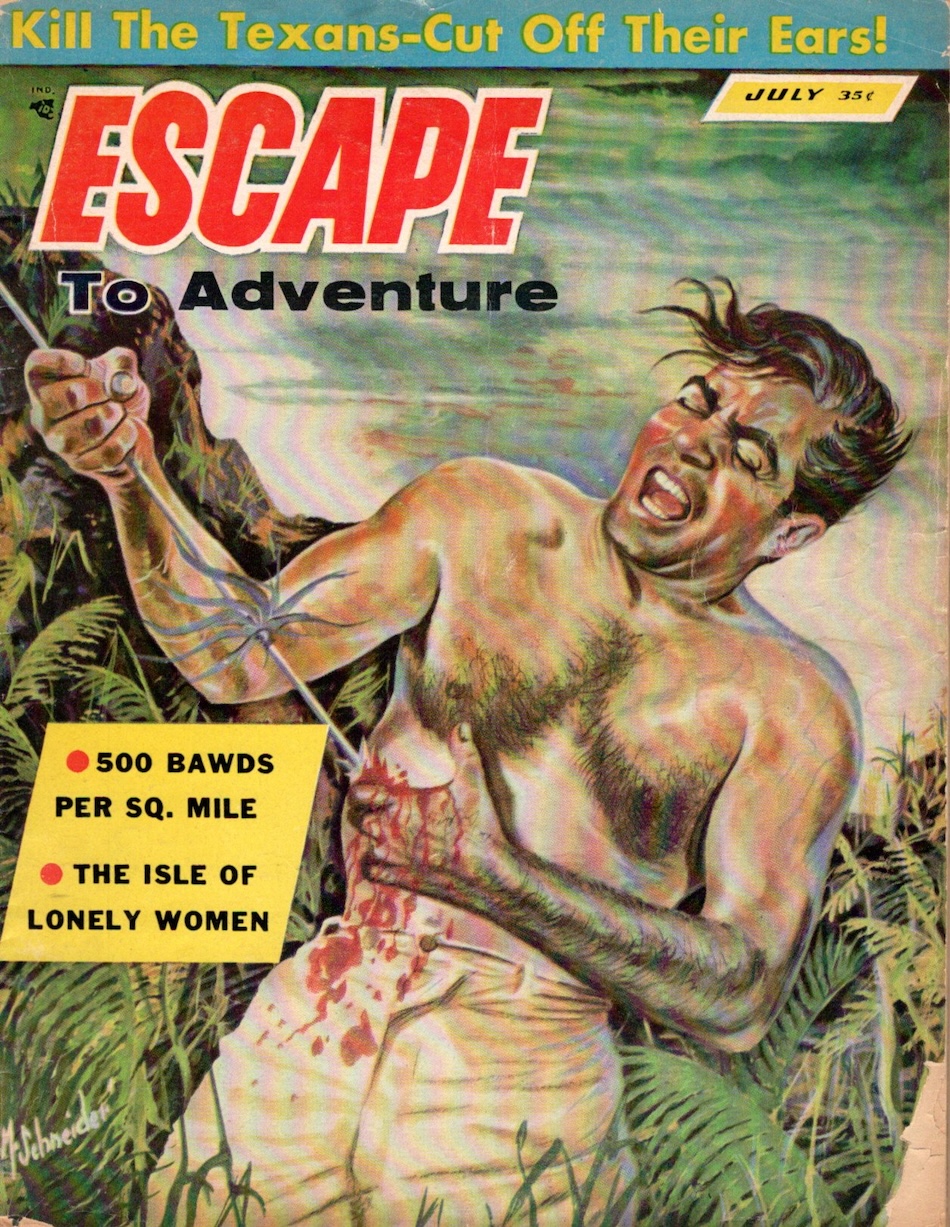

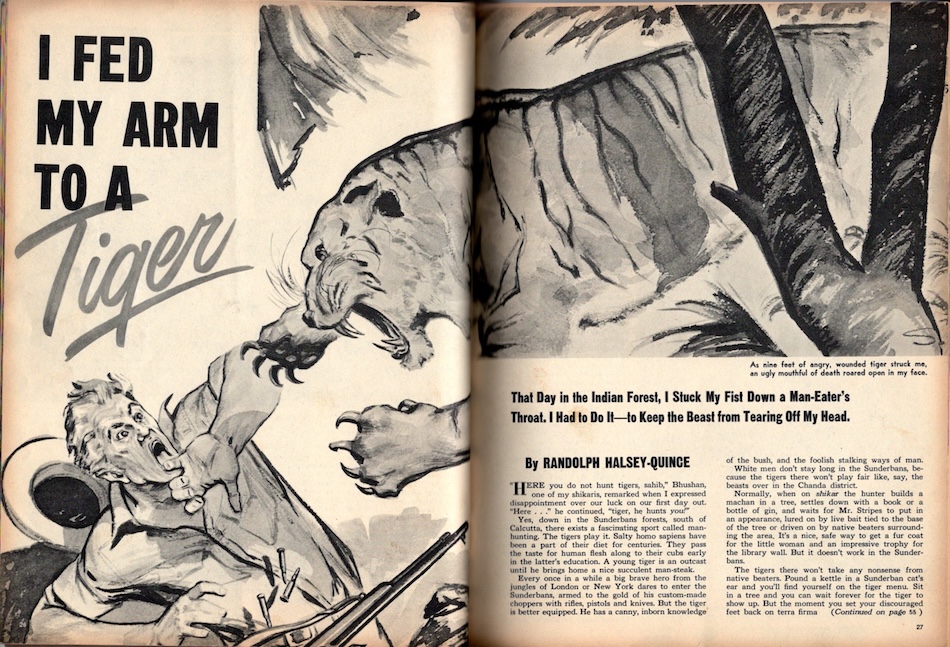

John contacted Jackinson in 1954, fresh from the army, and determined to travel and write. Jackinson thought John’s travel articles weren’t polished enough for the slick magazines like Post or Collier’s, and that he needed “an apprenticeship in the lesser books. For him that meant the men’s group.” There was, he told him, a ready market “for authentic and exciting first-person adventure yarns, so that armchair-tied clerks might turn into Lowell Thomases.”

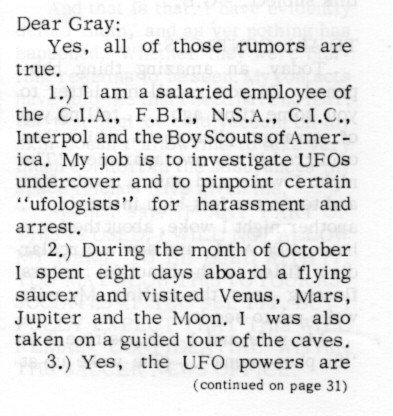

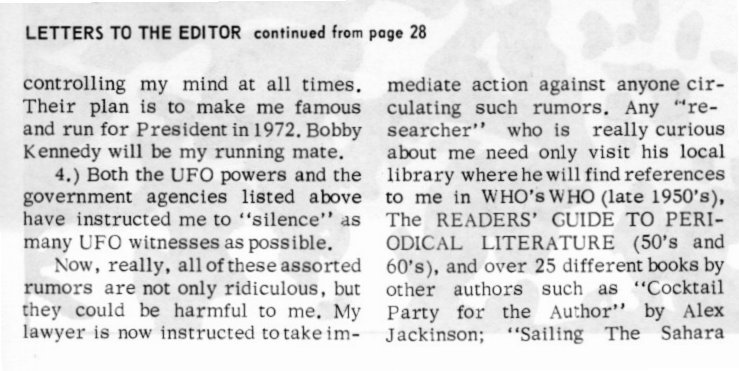

John was willing, asking, “How much must be true? How much can be invented?” Jackinson replied “with what knowledge I had. Nothing must be offered which could be proven wrong. Each adventure had to read as though it might have happened.”

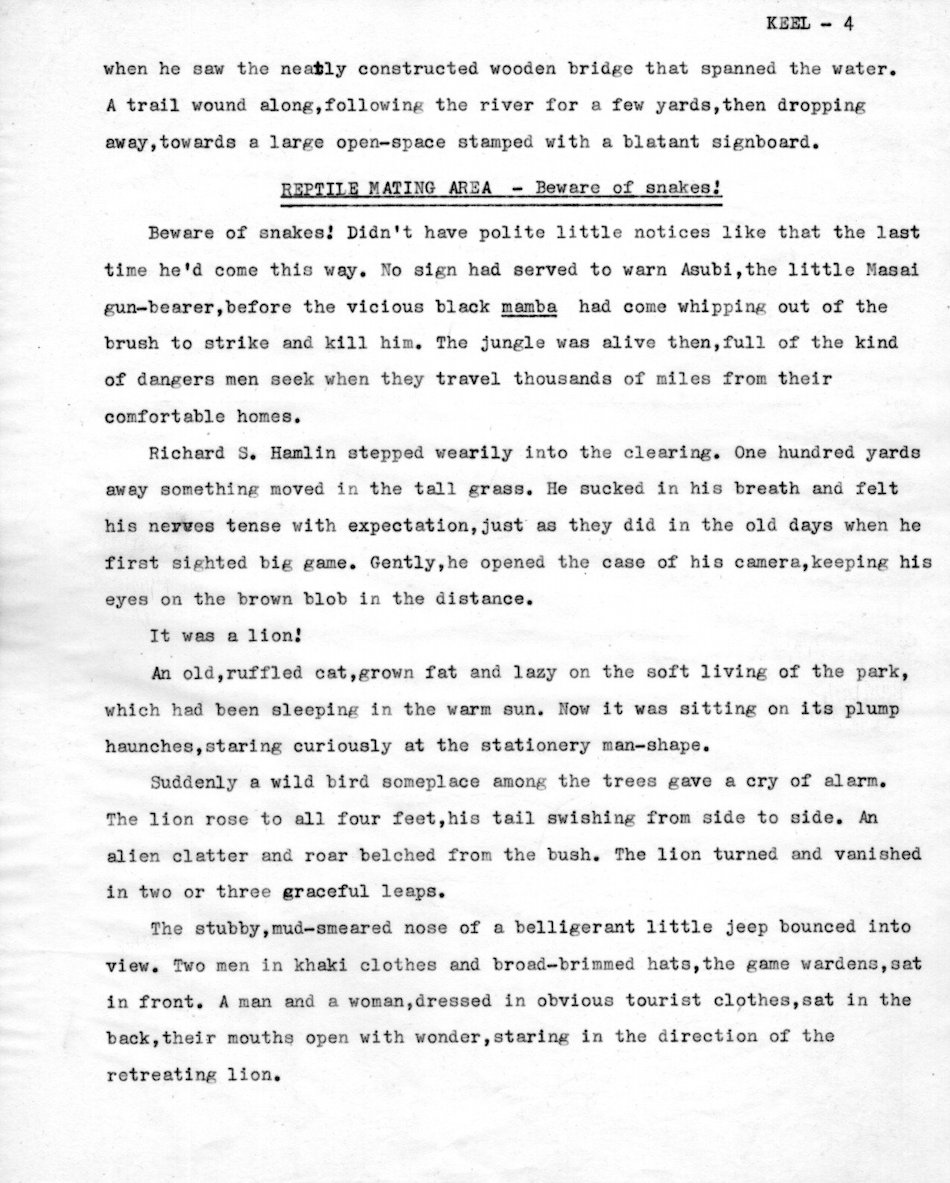

John set to work, writing and rewriting. “Keel caught the ‘formula’ very ably, and there is most definitely a formula involved. Because he wrote in a way that generated excitement, and because he was meeting a market need, editors were ready to meet him halfway.” After several pieces had been published, Jackinson suggested a book, which John first called Pattern for Adventure. An early pitch went nowhere; a year later, Jackinson felt he had “something submittable,” and set up a meeting with Howard Goodkind of Julian Messner.

Goodkind was interested, but asked, “How do we know this guy isn’t lying?” He was understandably wary; some popular books had turned out to be hoaxes, much to their publishers’ embarrassment: the memoirs of Joan Lowell and Trader Horn, for example. Jackinson explained that John mixed fact and fiction: “No incident is invented, just built dramatically from something that happened.” Goodkind decided to take the book, adding, “I’ll say this–he’s certainly a good writer.”

Jackinson stresses, “Keel achieved in months what most writers do not achieve in years,” although, of course, John had been writing seriously for much longer.

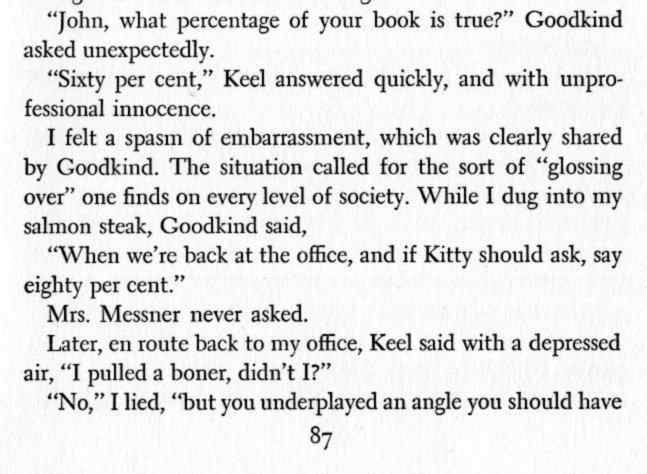

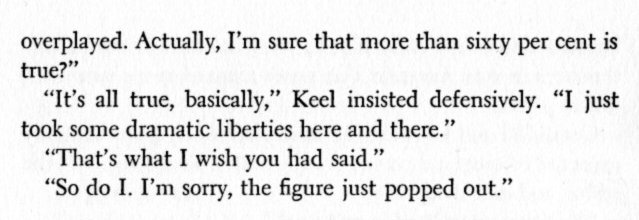

When John returned to NY, Jackinson set up lunch with Goodkind, who was surprised that the supposed swashbuckler was quiet and “skinny enough to be compared to a banana.” Goodkind returned to the question of the book’s veracity.

So, the percentage of Jadoo that is true is either sixty or eighty per cent; take your choice. But the other per cent is the embroidery; he really did have those adventures. Jackinson also reveals how much money Jadoo made. Comparing it to his other clients’ books, he says: “Jadoo did much better, but far short of expectations. With all the extra [magazine] sales, total income for Keel was around three thousand.” In the last chapter, he sums up John’s career after that: his subsequent dry spell, his plans to travel to Timbuctu or Yemen, and his work for television. His interest in UFOs was yet to come.

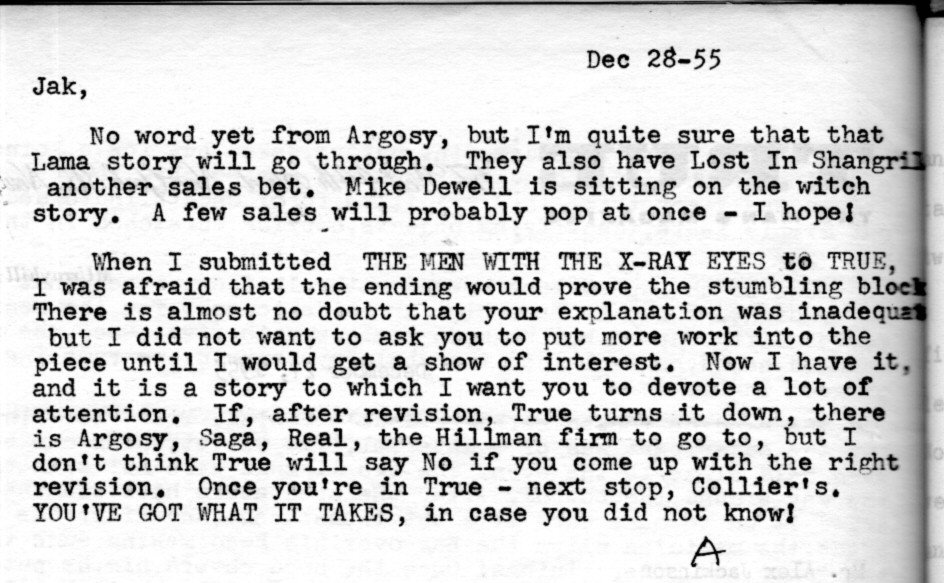

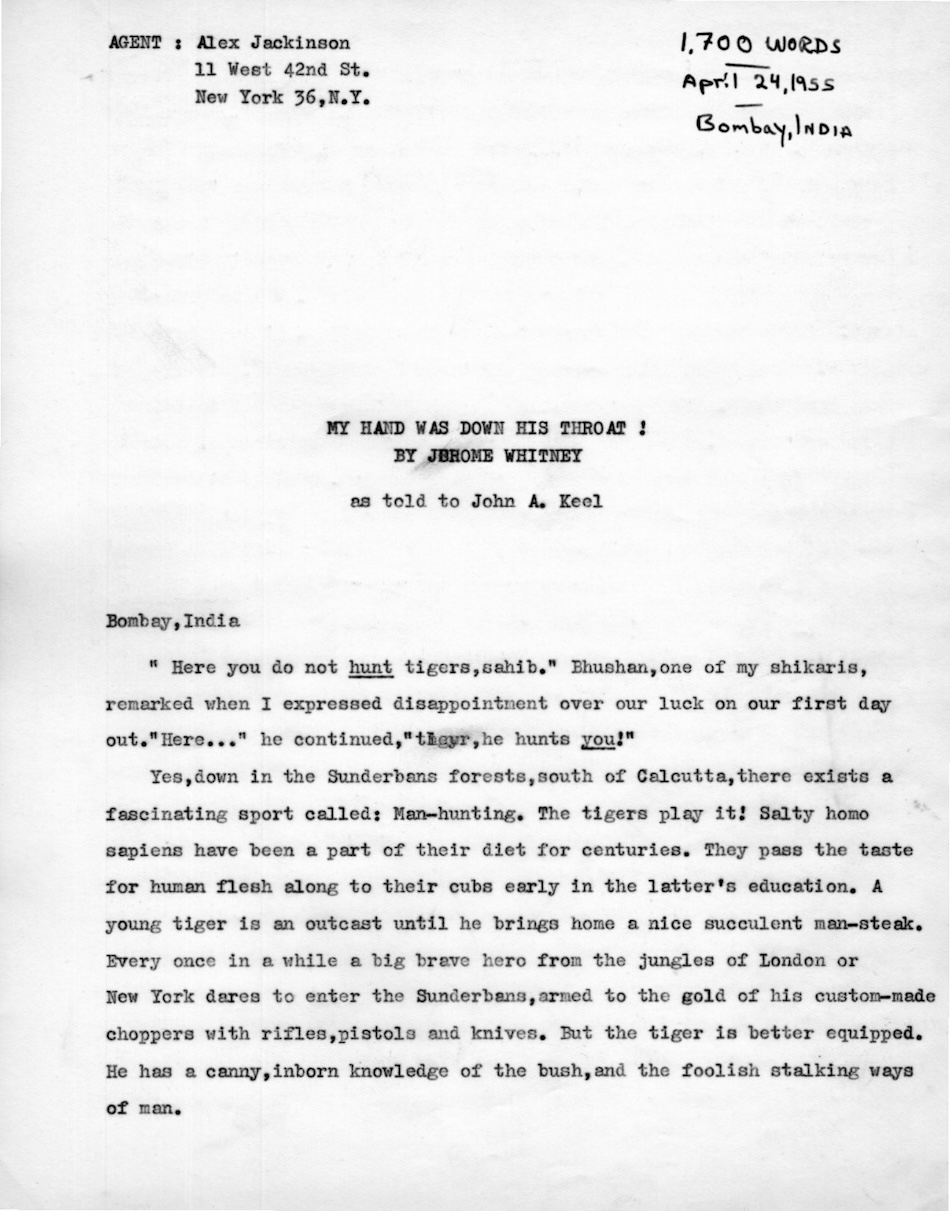

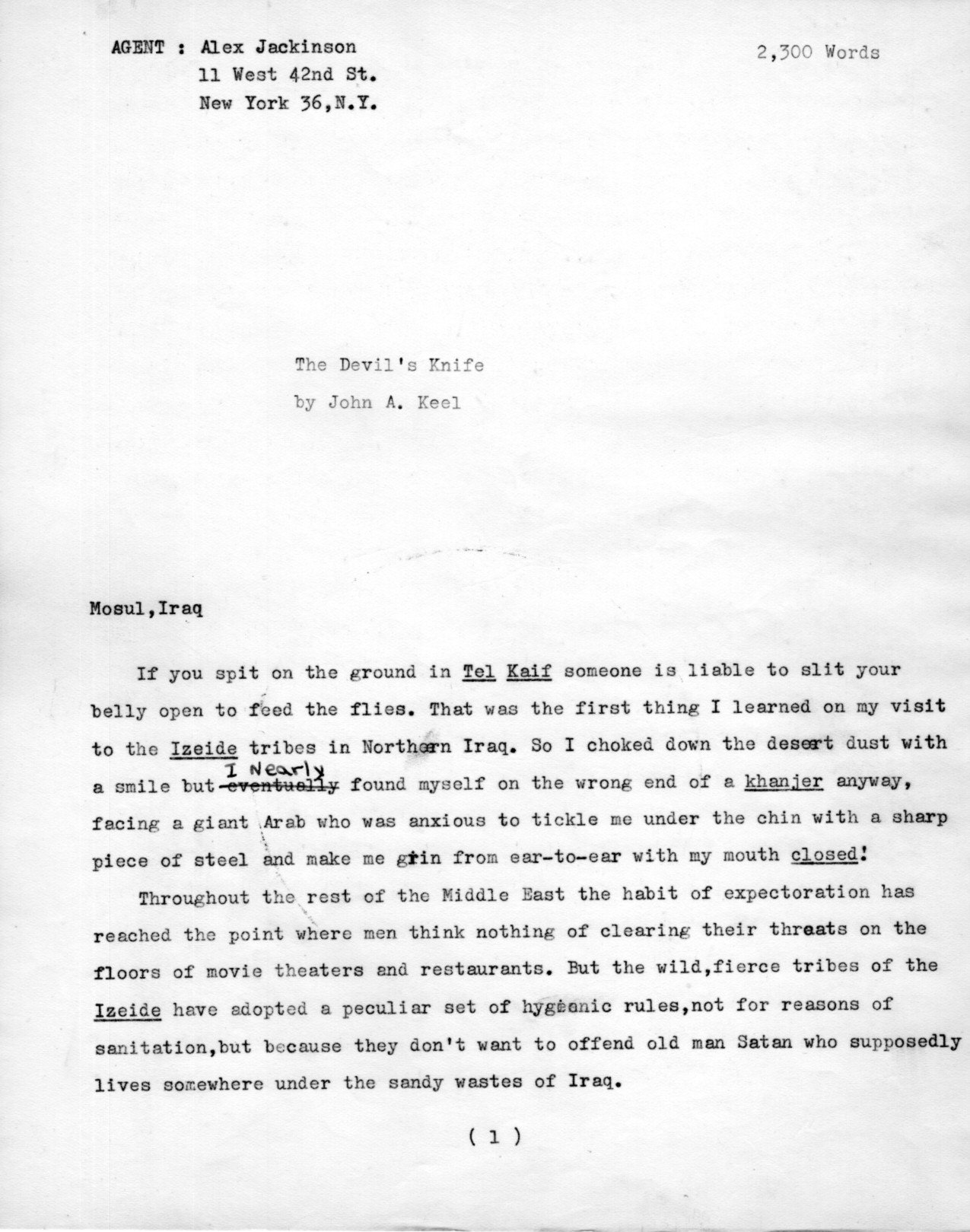

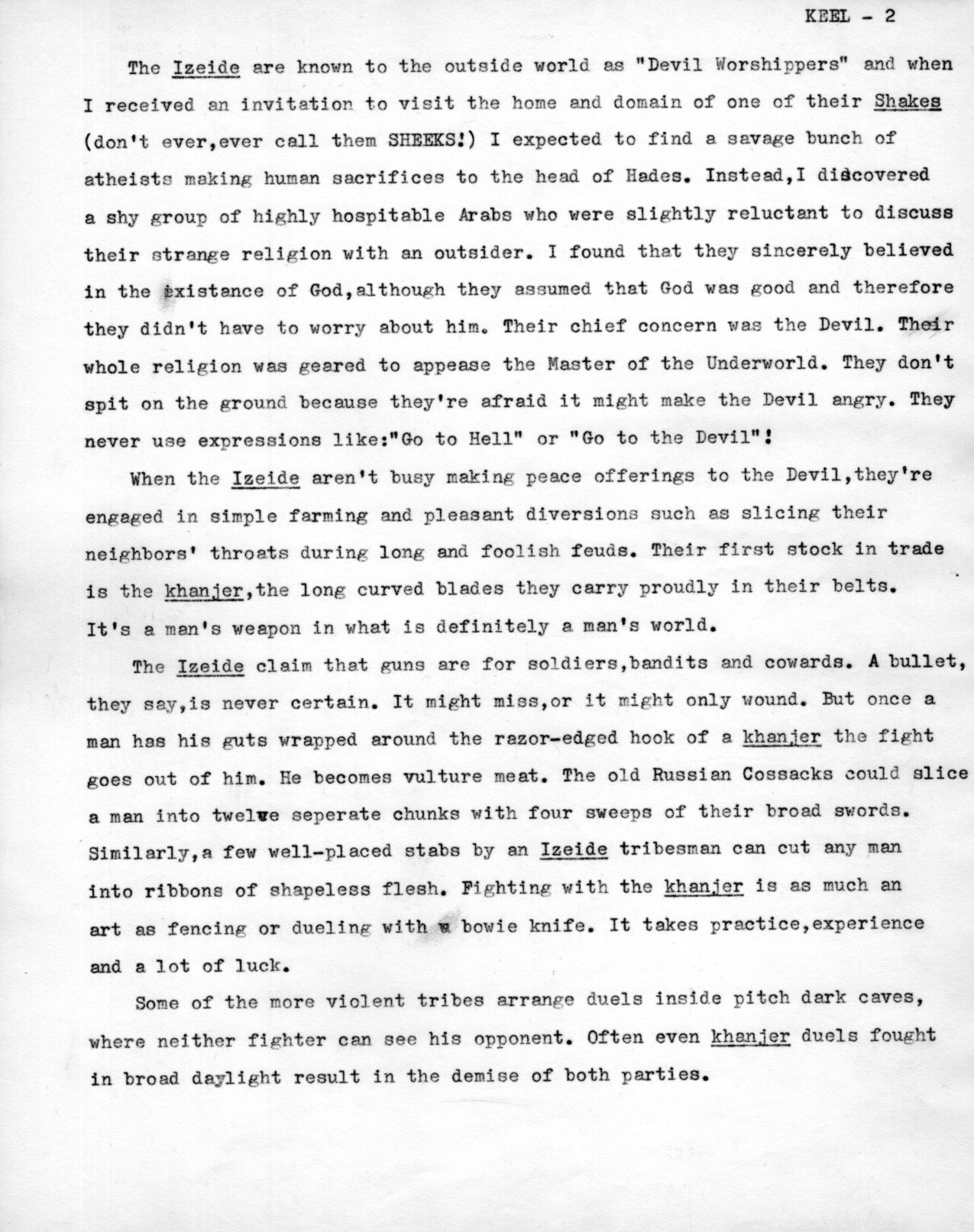

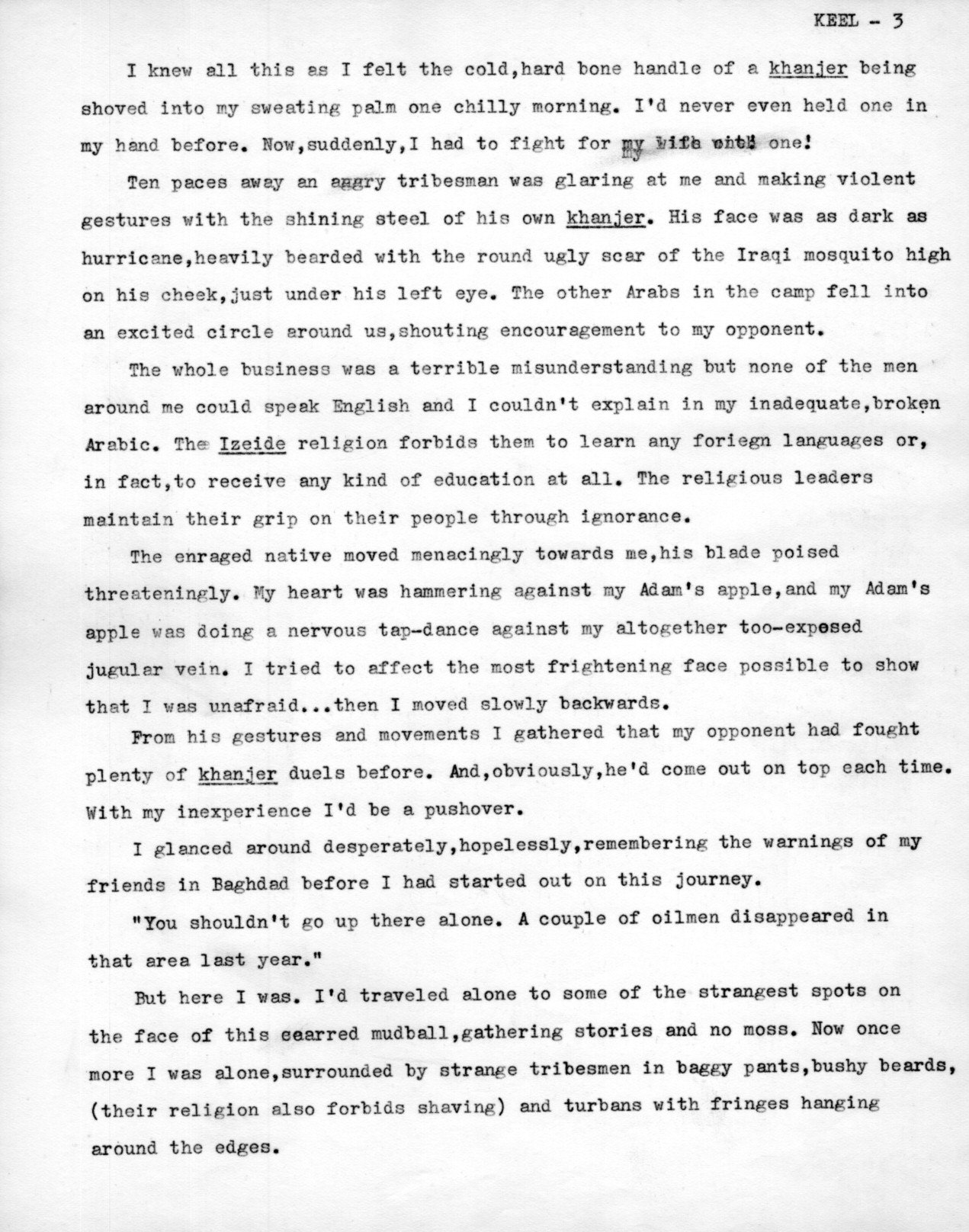

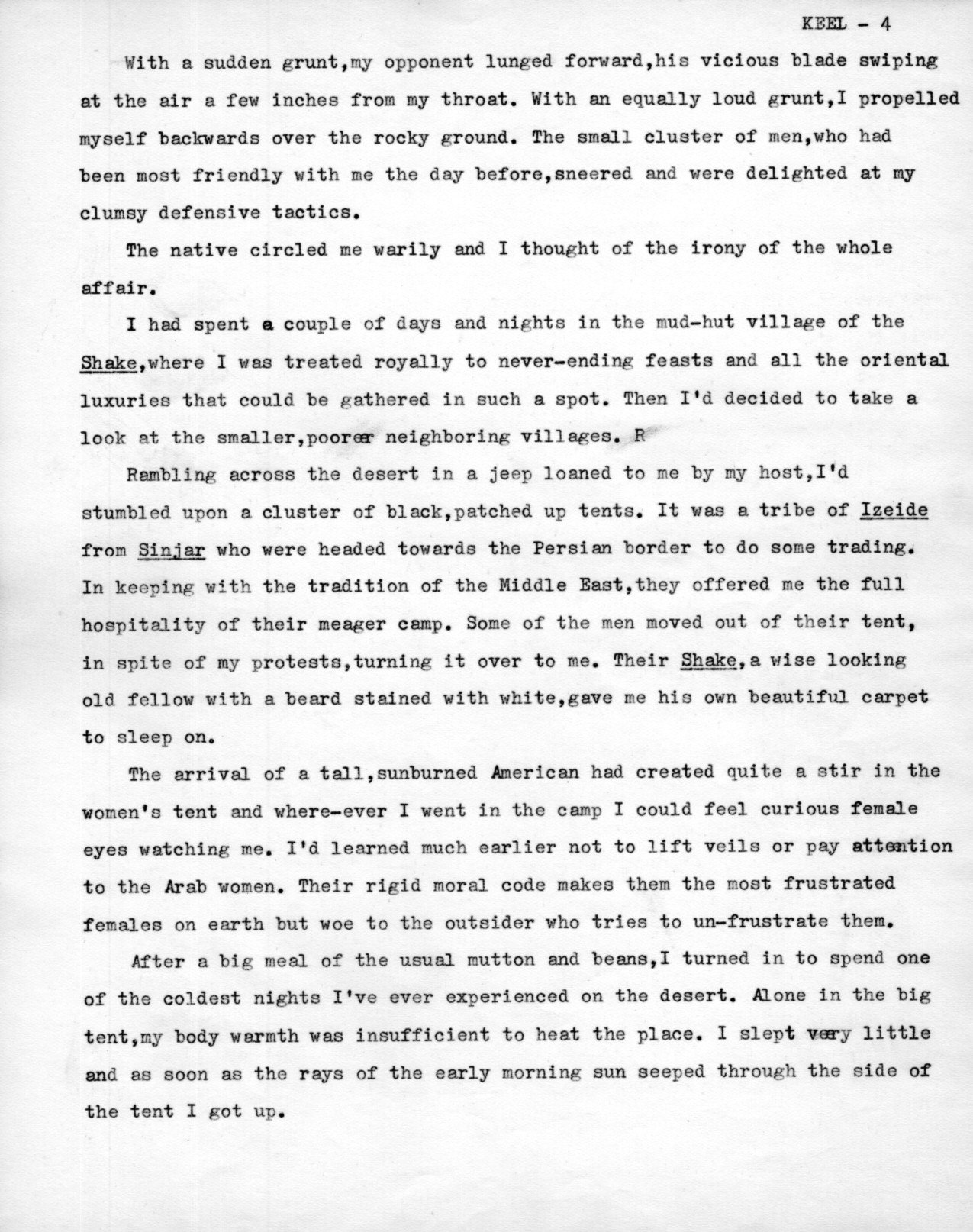

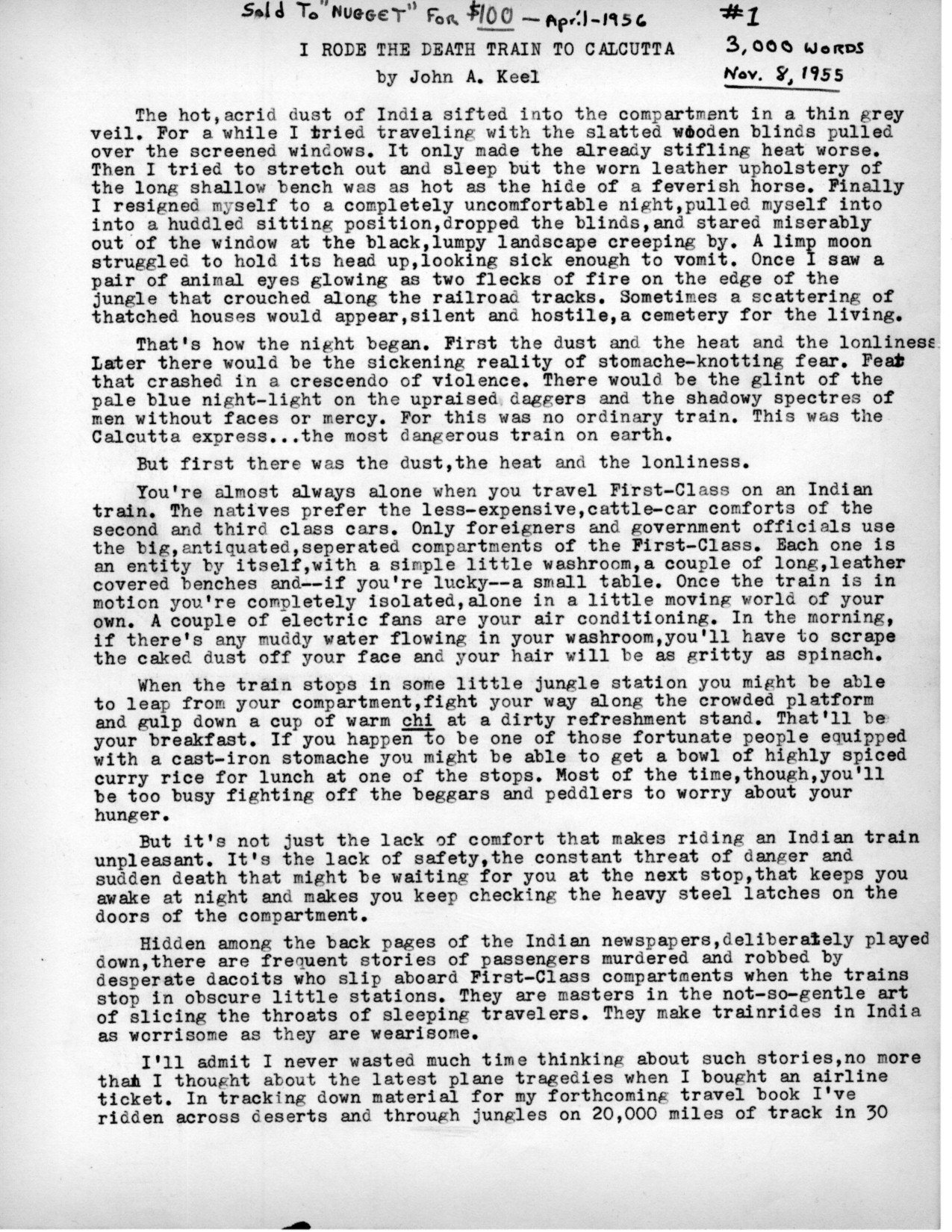

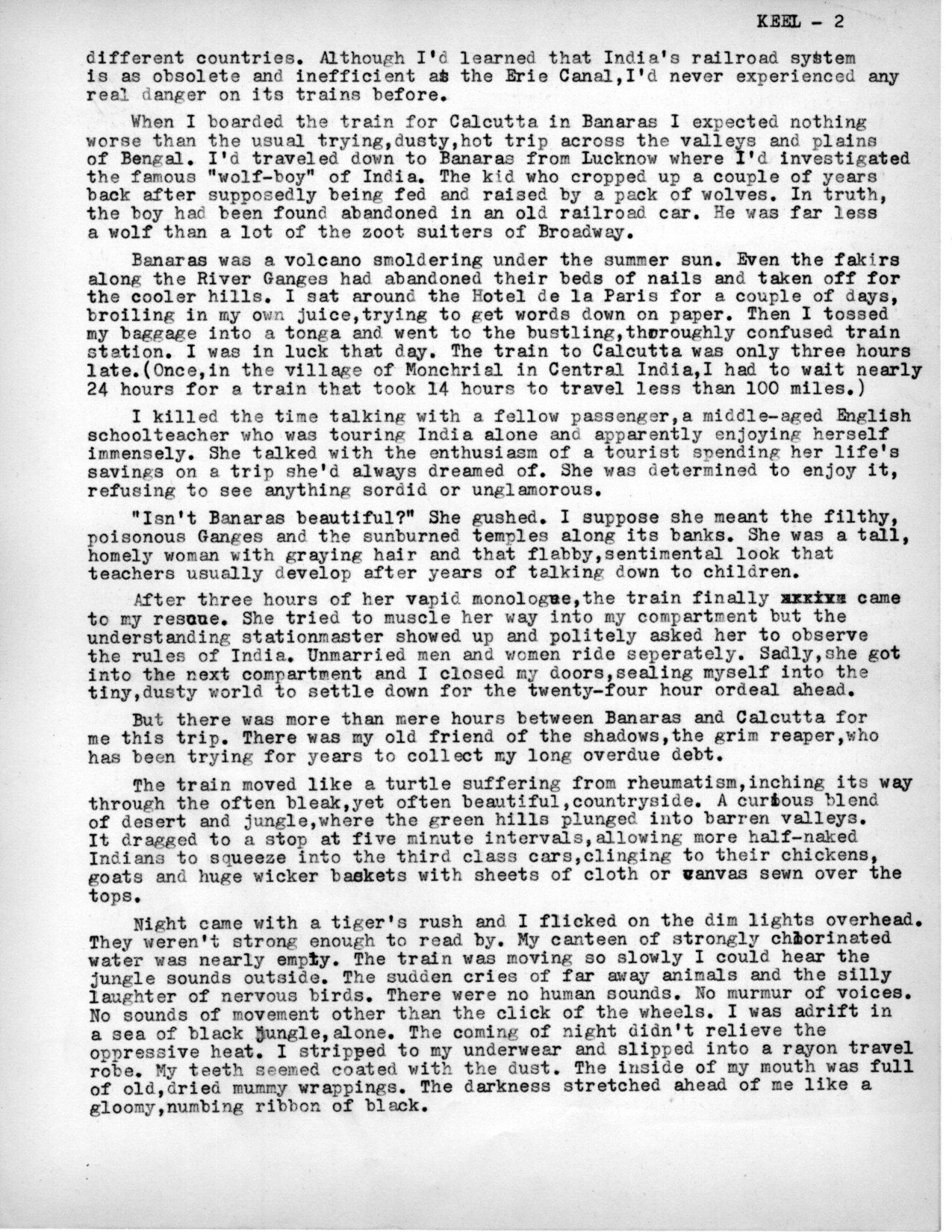

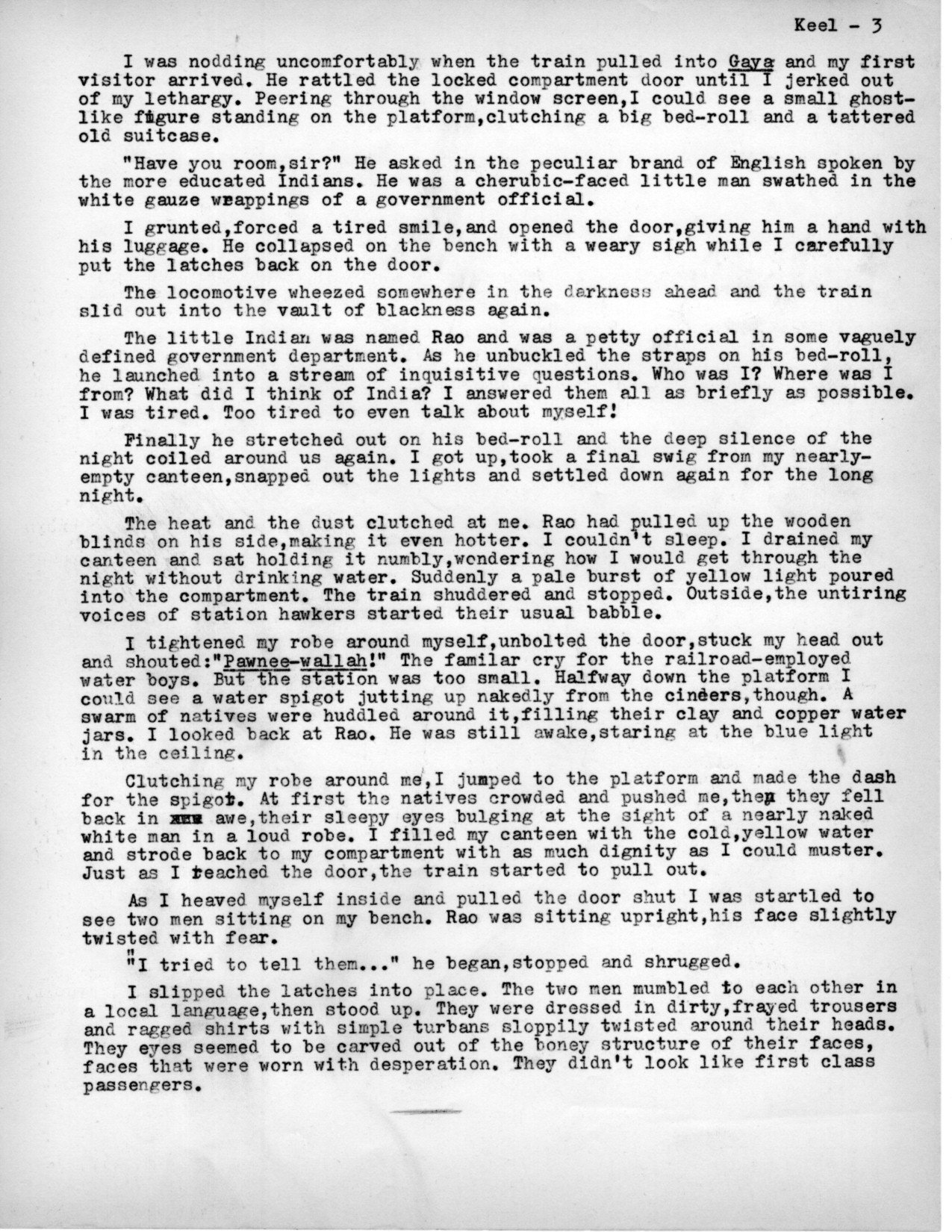

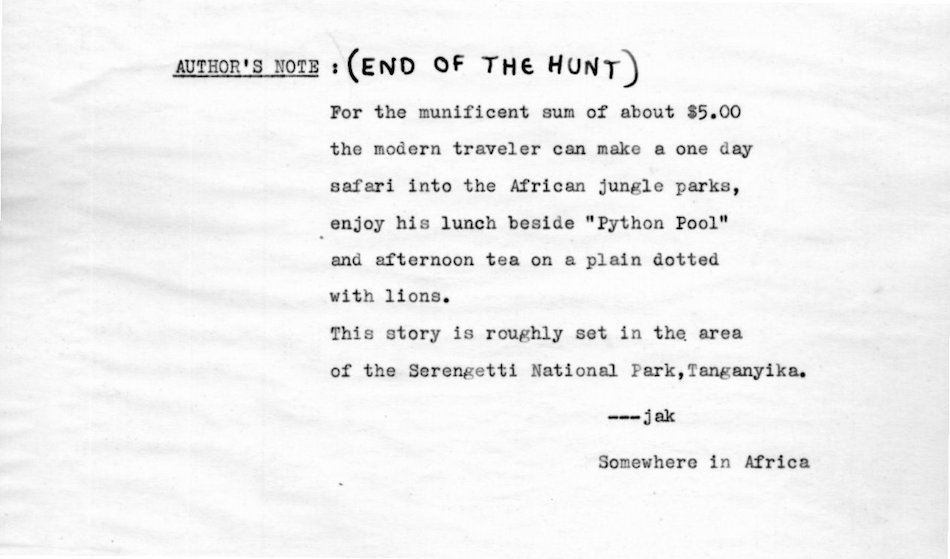

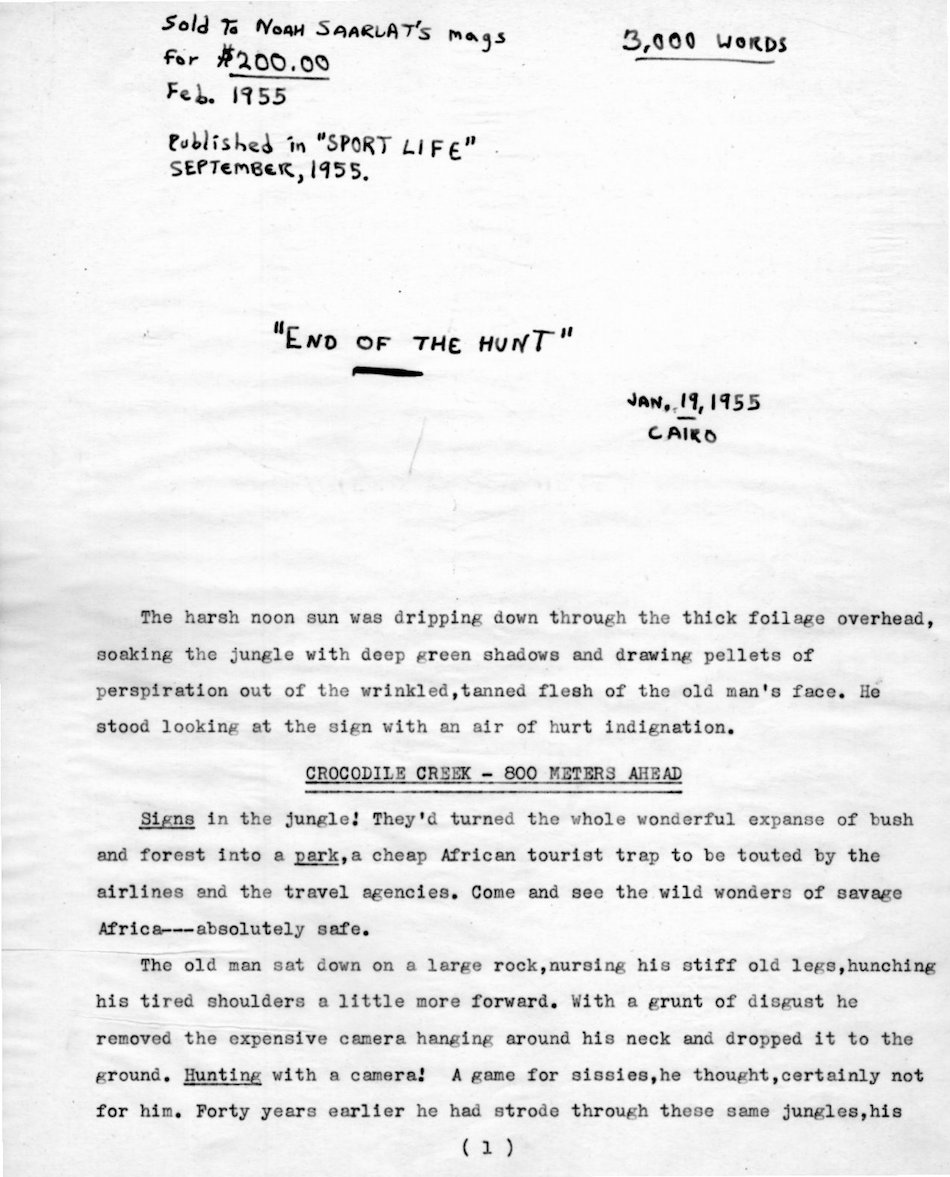

John himself wrote about this period in his article “Bosoms, Blood, and Baloney.” He also kept a binder labeled “1955,” in which he kept all the stories he wrote that year, with notes on the magazines that bought them and what they paid, as well as feedback from editors. Here’s a note from Jackinson about “The Men with the X-Ray Eyes,” which had been rejected by True. John rewrote it, and did eventually sell it to Man’s Challenge for $150. As Jackinson notes about John’s success in the book, “It was not easy. Nothing pertaining to writing is.”