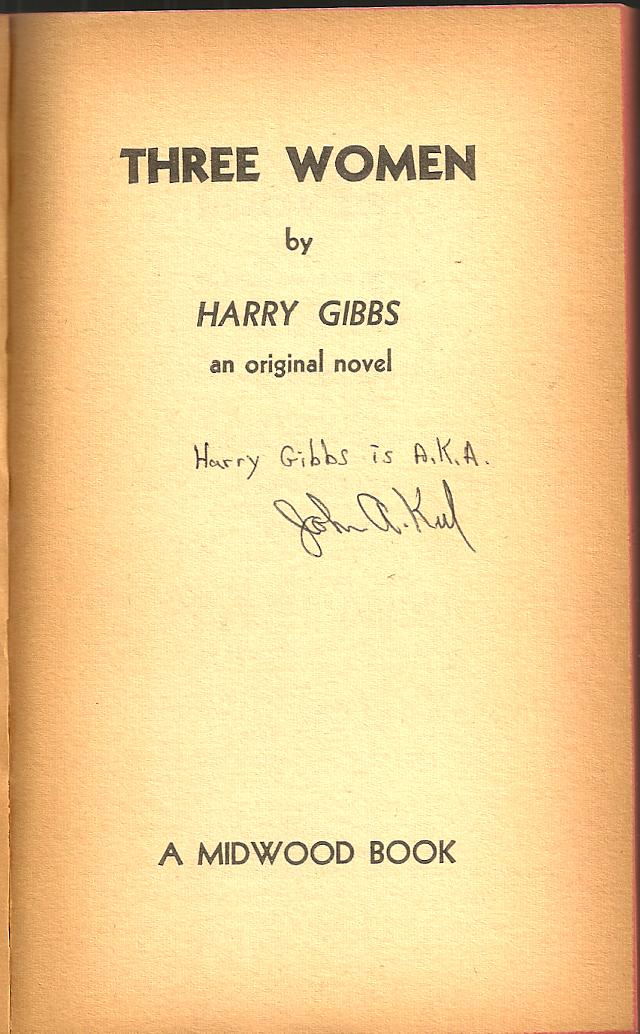

The movie of The Mothman Prophecies inspired many new editions of the book. Not only was it republished in the US and the UK; it was translated into French, Spanish, Italian, German, Japanese, and other languages. John was particularly amused by the Bulgarian edition; “I’m very big in Bulgaria,” he liked to say.

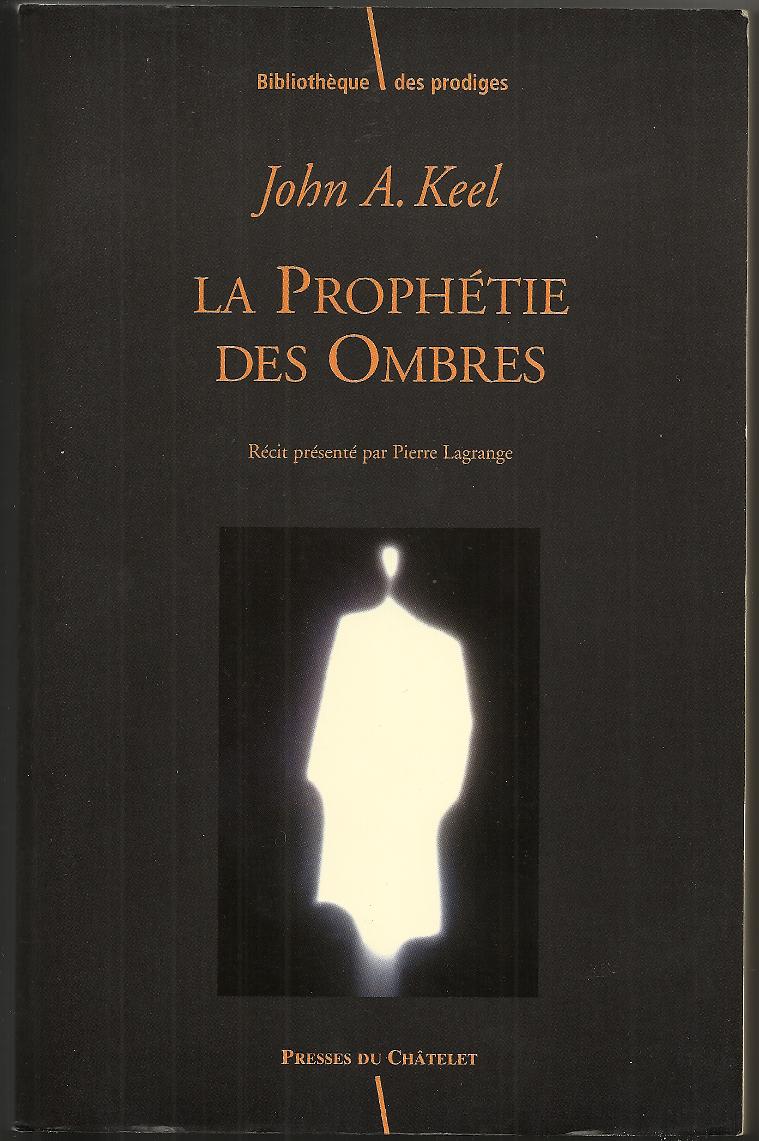

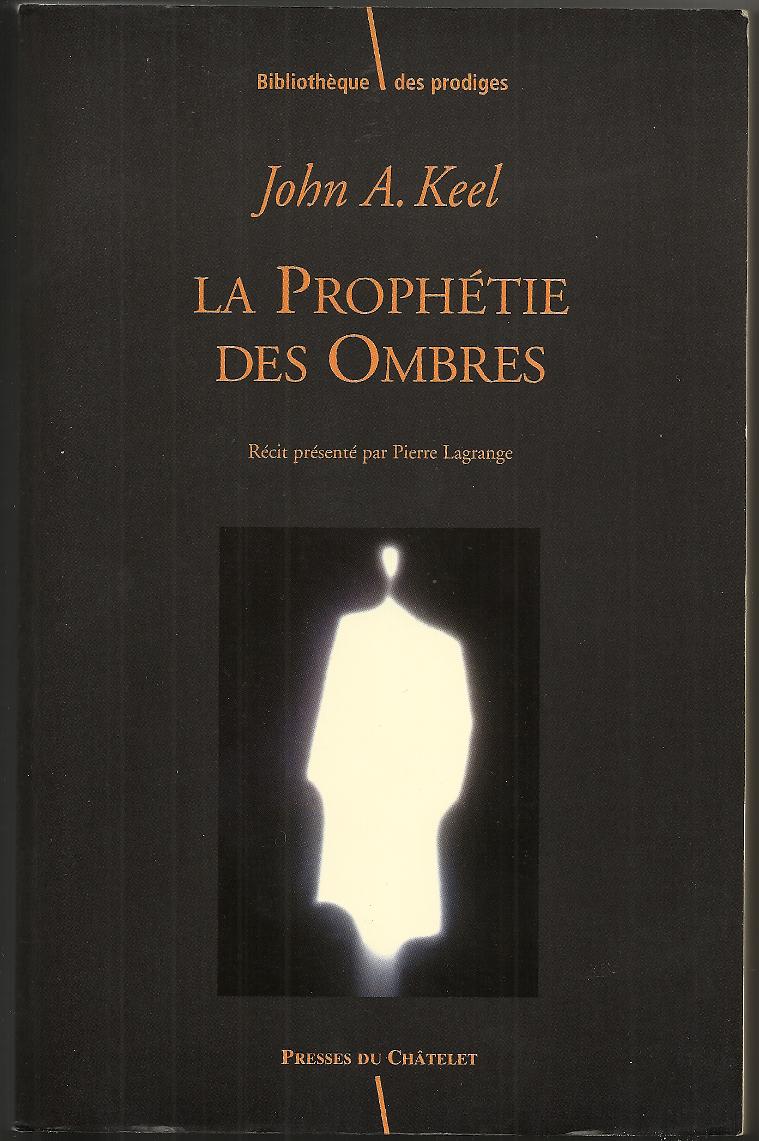

Most of them were simply translations of the text; some included a few film stills. The French edition (Presses du Châtelet, 2002) was more ambitious: it was the first volume of a projected Bibliothèque des prodiges (Library of Wonders) that intended to “do for occultism and ‘pseudo-science’ what others had done previously for erotica: to confer upon them the status of a literary genre, and to recognize their place in our cultural history.” It was a promising idea, but short-lived: the second and last entry in the series was Gray Barker’s They Knew Too Much About Flying Saucers.

The French title is La Prophétie des Ombres (The Shadow Prophecy). The literal translation — Les Prophéties de l’Homme-Phalène — would have been cumbersome, to say the least.

The translation (by Benjamin Legrand) seems fine to me, but what makes this edition noteworthy is the critical apparatus added by the editor of the series, Pierre Lagrange. It comprises a 19-page foreword, 40 pages of notes, a 9-page bibliography (by George Eberhart), and a 9-page index. The notes add much supplemental material on the many ufological personalities that pass through the book, and provide French readers with a thumbnail guide to the colorful UFO scene of the time. Lagrange’s bio describes him as “a sociologist of the sciences, specializing in the study of controversies about the paranormal, and a researcher associated with the Laboratory of Anthropology and History, Institute of Culture.” He’s published “numerous academic articles,” and two histories of ufological controversies.

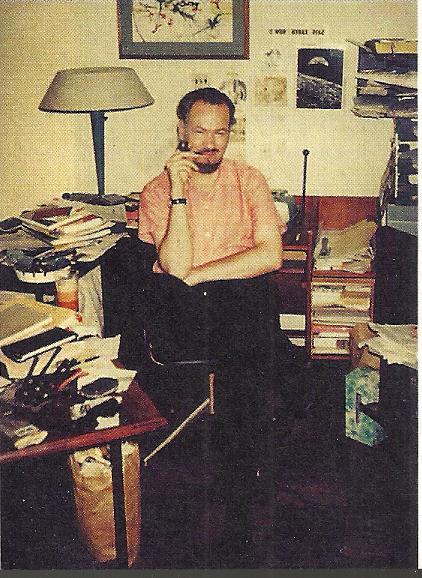

I summarized the foreword for John, who didn’t speak French, and was naturally curious about it. He liked it so much that he wanted to use it as the introduction to his last book, The Best of John Keel. This idea didn’t pan out, for a number of reasons: it was too long, he didn’t have the rights to it, and didn’t know how to contact Lagrange, to name a few. It’s worth reading; it’s a perceptive study of John’s ideas, particularly in The Mothman Prophecies and The Eighth Tower, and of his relations with the rest of ufology. And it ends with a glimpse of what it was like to try to set up an appointment with John (here in my translation):

“In fact, I haven’t told you under what circumstances I made the acquaintance of John Keel. In 1987, my laboratory sent me to the United States to inquire about UFO enthusiasts. I wanted to meet Keel. When I announced my intentions to ufologists in Paris, they looked at me in astonishmant, and told me that Keel had died. Unhappy news! But, according to other sources, he was indeed still alive. When I arrived in New York, I tried to call him. He was not at home, so I left a message on his machine. No news. I called again, and this time found him at home. He explained that he had called my number, and spoken to a woman who had promised to give me the message. But there was no woman in the apartment where I was staying. “Well, well, that’s curious,” remarked Keel, who insisted on asking for the details of this event, which he found extremely strange. I told him that he must have dialed a wrong number, but he denied this, and claimed that the person seemed to know me. I ignored this event, which, to me, was not one, and proposed a meeting.”